Physics at Weston

Personal recollections from the first Fermilab Theory Group: A tale of intrigue and discovery

Louis Clavelli, The University of Alabama

Louis Clavelli, The University of Alabama

The early days at 27 Sauk

It was early in September, 1969, that Estelle and I piled most of our belongings into our Chevrolet and set out on the road from New Haven to the National Accelerator Laboratory (NAL) now known colloquially as Fermilab. It was an early step for me in what was to be a long career as a student of physics. I was part of a tradition of physicists willingly going to remote places for the chance to participate in the advancement of the science. Sadly, some of this tradition seems now to have faded as illustrated by the difficulty that the ill-fated Superconducting Super Collider had in attracting good people to Texas. In 1969, Fermilab was already triggering a great modernization of many midwestern physics departments, a role that the aborted SSC would have played for the southern and mountain states. For me, to be fair, the far western suburbs of Chicago were not as remote as they probably seemed to many others. I had a fondness for the city from my days as a graduate student at the University of Chicago and even had friends and relatives in the area.

In the midst of a proverbial midwestern thunderstorm, Estelle and I arrived tired and confused on the evening of September 3. The rain was coming down in torrents and, at one point, it seemed that the road was filled with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of equally confused and frantically hopping frogs. After searching for about an hour for a motel east of the lab and spending a night in what is probably still the only motel on that side, we checked into a motel on Farnsworth Avenue in Aurora. About thirty feet from the motel room window began the great midwestern corn field that stretches from Fermilab for hundreds of miles. The corn was already six feet high and begging to be harvested.

Fermilab, then as now, offered a generous temporary housing allowance so Estelle and I had the luxury of not having to take the first apartment that became available. We moved into a comfortable, upper corner unit at Carriage Drive Apartments, now known as Aspen Ridge. The units were located in the town of West Chicago at the intersection of route 59 and Roosevelt road. Nowadays, there is a substantial cloverleaf there which, incidentally, encloses an authentic Italian Restaurant, Luigi's Pizza and Spaghetti, serving what is possibly the best real food in the Fermilab area. The leading employer in West Chicago at that time was Campbell Soup's mushroom factory. Its employees were primarily Mexican immigrants working their way up the American social ladder. They have done well; today it is as easy to hear Spanish as English at Aspen Ridge.

In the midst of a proverbial midwestern thunderstorm, Estelle and I arrived tired and confused on the evening of September 3. The rain was coming down in torrents and, at one point, it seemed that the road was filled with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of equally confused and frantically hopping frogs. After searching for about an hour for a motel east of the lab and spending a night in what is probably still the only motel on that side, we checked into a motel on Farnsworth Avenue in Aurora. About thirty feet from the motel room window began the great midwestern corn field that stretches from Fermilab for hundreds of miles. The corn was already six feet high and begging to be harvested.

Fermilab, then as now, offered a generous temporary housing allowance so Estelle and I had the luxury of not having to take the first apartment that became available. We moved into a comfortable, upper corner unit at Carriage Drive Apartments, now known as Aspen Ridge. The units were located in the town of West Chicago at the intersection of route 59 and Roosevelt road. Nowadays, there is a substantial cloverleaf there which, incidentally, encloses an authentic Italian Restaurant, Luigi's Pizza and Spaghetti, serving what is possibly the best real food in the Fermilab area. The leading employer in West Chicago at that time was Campbell Soup's mushroom factory. Its employees were primarily Mexican immigrants working their way up the American social ladder. They have done well; today it is as easy to hear Spanish as English at Aspen Ridge.

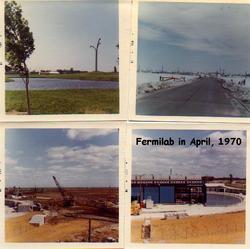

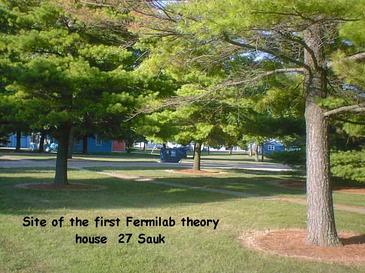

On the second day after our arrival, I was directed to the Theory Building or, more accurately, the Theory Cottage at 27 Sauk in Weston Village. The town of Weston had been a failing real estate venture before its developers were rescued by being bought out by Fermilab. It consisted of some 30 to 50 one floor, six room houses hastily built on thin concrete slabs. The houses were poorly insulated from the summer heat and winter cold. Some inefficient window air-conditioning units were in place. It was not unheard of to find in some of the houses big gaps between the floor and the wall. It is now known as Fermilab Village or just the "Village" but it should not be confused with New York's Greenwich "Village".

David Gordon had already preceded me by seven weeks and had set up office in the former master bedroom of the theory house. He had a nice view of Sauk Boulevard, a dusty two lane road leading into the village without the mature trees one sees today. I chose for my office the former kitchen of the house from which all cabinets and plumbing had been removed. The kitchen was at the back of the house and had the advantage of a door leading directly to the parking lot.

Within the next two weeks, the complete theory group had assembled. We were, in alphabetical order, myself, Louis Clavelli, David Gordon, Pierre Ramond, Jim Swank, and Don Weingarten. I had studied with Yoichiro Nambu at Chicago and had, afterwards, worked as a post-doc at Yale. David had been a Brandeis student and had done post-doctoral work with Fubini and Veneziano. David's physics discourse was peppered with the strange sounding phrase "how to say?". It was only much later that I realized this was a literal translation of the Italian idiom "come dire?". Pierre was from Balachandran's group at Syracuse. Jim had studied with Nishijima at the University of Illinois and Don with Bob Serber at Columbia. Pierre took an apartment in Wheaton, Illinois, home of Wheaton College, the alma mater of Billy Graham. David bought a stylish yellow stucco house in Warrenville. Don could not make the leap from New York City to the western suburbs of Chicago. He found a place in Hyde Park and willingly drove an hour each way to work and back. Pierre was the last to arrive and therefore got, by default, the back bedroom of the theory house. There was a friendly informality among the group members; Jim sometimes came through my office to use the back door to the parking lot. The western suburbs did not offer much in professional opportunities to spouses. Estelle did find a teaching job in Winfield but Jean Swank, herself a talented physicist, had to drive an hour each way to teach at Chicago State College. Lillian Ramond, an engineer, found no professional outlet for her talents nor did Ann Gordon who happened to be the sister of Mary of Peter, Paul, and Mary fame. Don Weingarten was still enjoying the bachelor life.

Most of the group met for the first time on Sauk Boulevard but, Pierre and I had met by chance a couple of months prior to that at the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste. I remember sitting in the main square drinking coffee with Giovanni Venturi when Pierre, Gerhard Mack, and some of the Syracuse group passed by across the square. I pointed Pierre out to Gianni and mentioned that we were going to be colleagues at Fermilab that Fall. Gianni's first question was "Is he any good?". I had no way to know the real answer to that and responded something to the effect that I assumed so since he had a PhD. It turned out that Pierre was brilliant and we developed a close collaboration in the months to come.

The theory group was a unique experiment at Fermilab. It was designed to answer the question of what might happen if you assembled five, hand-picked and pedigreed, young physicists with no senior staff, gave them complete freedom to explore the frontier of theoretical physics with no computer facilities or archival library, fifty miles from the nearest physics department, but with a virtually unlimited budget to bring in expert consultants. Actually, the budget was not unlimited but most of us were never conscious of its boundaries. With the support of the lab we immediately set up a "professor of the month" program which brought in some of the most distinguished theoretical physicists in the country. Among them were Yang and Lee, Fubini and Veneziano, Sakurai, Chew, Mandelstam, and others. The professors of the month would each give a series of three or four lectures on current topics in particle theory. Often some of the experimental staff would come but sometimes just the five of us sat in front of the visitors plying them with questions and trying to distill something from their wisdom. We were, all five, determined to contribute some good ideas to theoretical physics although, then as now, nobody knew just what a good idea was physiologically or how one got one or how much credit one deserved for getting one. In addition to the professor of the month program and the laboratory colloquium which was often concerned with accelerator technology, we frequently brought in speakers for individual theory seminars. There was tremendous hope for Fermilab throughout the physics community and we never had trouble finding good theorists who would come to speak to us in return for a tour of the laboratory under construction. The group would often take the speaker to a silo on one side of the main ring from which one got a good view of the construction. Climbing the silo rapidly became tedious for us but there wasn't a lot else to show visitors to the corn belt. The laboratory directorate thought that showing visitors around was one of the primary roles of a theory group so we often entertained experimental as well as theoretical guests. It is said that Roy Schwitters also shared this view when he initiated the first (and last) theory group at the SSC in Texas. On one occasion we had Holger Nielsen of the Niels Bohr Institute give a Fermilab theory seminar. Later that evening, Don found him wandering confused around Hyde Park and invited him for a beer at Jimmy's Bar. It turned out to be an important contact. On another occasion we invited Andre Neveu and Joel Sherk to come together from Princeton. These two had done their math homework at the Ecole Normale and in 1970 were making great strides in understanding dual loop graphs. Our own travel budget was similarly generous. We traveled frequently to APS meetings. In addition there were frequent car trips to talk to Nambu and Freund at Chicago, Boris Kayser at Northwestern, and once to Madison to speak with Miguel Virasoro about the developing string theory. We also talked occasionally with Carl Albright who had just started a particle theory effort at Northern Illinois University. On one occasion Nambu invited Pierre and I to lunch at the University of Chicago Quadrangle Club.

In the former living room of 27 Sauk, our secretary, Vickie Caffee, had her desk. She was bright and professional but, sometimes, at least to Pierre, it seemed as if she felt her role was to keep the five of us focussed on laboratory business. What we were doing was far closer to the purpose of the laboratory than the daily work of designing bunkers and tunnels that was going on around us but Vickie wasn't quite sure. Nevertheless, she was awed by our ability to fill blackboards with equations and addressed us respectfully as Dr. Clavelli, Dr. Gordon etc. We, of course, referred to each other more informally. It was Dr. Lou, Dr. Dave, Dr. Pierre, Dr. Jim, and Dr. Don.

In addition to the theorists, there was a much larger contingent of bright young experimentalists at Fermilab from the beginning. The best of these, or at least the ones who were friendliest to theorists, were Joe Lach, Taiji Yamanouchi, Muzaffer Atac and Dick Carrigan. Taiji was especially known to us as one with boundless empathy for people, especially for people devoted to physics. Muzaffer and his young family resided across from Estelle and me at Carriage Drive.

Bob Wilson, Fermilab's first director, in addition to professing to believe in the importance of theoretical physics, wanted to have a strong experimental physics staff even before the machine was built. He achieved this by hiring experimental physicists for many of the jobs that could have been done, perhaps better, by electrical and civil engineers. In principle they each had 50% time free to pursue experiments at other functioning laboratories but in practice most of them became totally absorbed by the huge task of building the machine. Sometimes Dick Carrigan would pull from his center desk drawer a graph of some data from deep-inelastic scattering suggesting that the intermediate weak boson might be found at a mass of 10 GeV. However, for the most part, it was difficult to engage the experimentalists in discussions about particle physics until the machine was about to turn on.

In the beginning there was a spirit of egalitarianism among the five theorists. Although some of us had had post-doctoral experience and others had come straight from the PhD, there were, as far as we know, no differences in our appointments. However, it was obvious to the lab, if not to us, that a point of contact was needed between the directorate and the theory group. Early in October of 1969, we were told that David Gordon had been chosen to lead the group in this sense. We received the news with indifference. None of us, as far as we knew, had administrative ambitions.

In addition our letters of appointment were vague about the exact nature of our positions. Although speaking of an initial term, they left the clear implication that we were expected to continue at Fermilab. The letters were vague but did not employ the terms in common usage then as now to indicate a strictly term appointment. For instance there was no use of the terms "Post-doctoral" or "Research Associate". In a tenure track appointment at a university, the awardee is to be considered for tenure after five years, even though at many if not all, there is an annual "retention" review. It seemed to us that our letters of appointment might have been the laboratory equivalent of this. We were, at first, indifferent to this vagueness. Although supposedly 1967 had been the last of the good years, we were totally ignorant of the collapse of the job market for theoretical physicists which was going on around us. Full of self confidence, we felt no need for job guarantees from the lab. We had all gone to graduate school in years when the job opportunities for theoretical physicists were seemingly growing without bound. I remember once in early 1969 meeting a panicked young physicist at Yale who had already sensed the growing crisis. I confidently assured him that there were plenty of universities seeking to build physics programs. His response was that that was OK for me but he had been a student at Yale and was expected by his family to become an ivy league professor.

There was always a religious aura surrounding Fermilab. The director's complex was the "Curia". Perhaps we have now totally confused the public by telling them that Fermilab is searching for the "God Particle". At any rate, in the late sixties, the praise of Bob Wilson resounded throughout Fermilab Village and the whole physics community. It would be a pale comparison to equate his status with that of the leader of the Roman Curia. It was said that the Fermilab hi-rise, then under construction, was purposely designed with some of the overtones of the medieval cathedrals. Everyone was free to construct his own private interpretation of this. I always took it to represent the hope that modern society would devote a similar percentage of its GNP to idealistic enterprises as the medieval societies did in building the cathedrals.

The theory group was a unique experiment at Fermilab. It was designed to answer the question of what might happen if you assembled five, hand-picked and pedigreed, young physicists with no senior staff, gave them complete freedom to explore the frontier of theoretical physics with no computer facilities or archival library, fifty miles from the nearest physics department, but with a virtually unlimited budget to bring in expert consultants. Actually, the budget was not unlimited but most of us were never conscious of its boundaries. With the support of the lab we immediately set up a "professor of the month" program which brought in some of the most distinguished theoretical physicists in the country. Among them were Yang and Lee, Fubini and Veneziano, Sakurai, Chew, Mandelstam, and others. The professors of the month would each give a series of three or four lectures on current topics in particle theory. Often some of the experimental staff would come but sometimes just the five of us sat in front of the visitors plying them with questions and trying to distill something from their wisdom. We were, all five, determined to contribute some good ideas to theoretical physics although, then as now, nobody knew just what a good idea was physiologically or how one got one or how much credit one deserved for getting one. In addition to the professor of the month program and the laboratory colloquium which was often concerned with accelerator technology, we frequently brought in speakers for individual theory seminars. There was tremendous hope for Fermilab throughout the physics community and we never had trouble finding good theorists who would come to speak to us in return for a tour of the laboratory under construction. The group would often take the speaker to a silo on one side of the main ring from which one got a good view of the construction. Climbing the silo rapidly became tedious for us but there wasn't a lot else to show visitors to the corn belt. The laboratory directorate thought that showing visitors around was one of the primary roles of a theory group so we often entertained experimental as well as theoretical guests. It is said that Roy Schwitters also shared this view when he initiated the first (and last) theory group at the SSC in Texas. On one occasion we had Holger Nielsen of the Niels Bohr Institute give a Fermilab theory seminar. Later that evening, Don found him wandering confused around Hyde Park and invited him for a beer at Jimmy's Bar. It turned out to be an important contact. On another occasion we invited Andre Neveu and Joel Sherk to come together from Princeton. These two had done their math homework at the Ecole Normale and in 1970 were making great strides in understanding dual loop graphs. Our own travel budget was similarly generous. We traveled frequently to APS meetings. In addition there were frequent car trips to talk to Nambu and Freund at Chicago, Boris Kayser at Northwestern, and once to Madison to speak with Miguel Virasoro about the developing string theory. We also talked occasionally with Carl Albright who had just started a particle theory effort at Northern Illinois University. On one occasion Nambu invited Pierre and I to lunch at the University of Chicago Quadrangle Club.

In the former living room of 27 Sauk, our secretary, Vickie Caffee, had her desk. She was bright and professional but, sometimes, at least to Pierre, it seemed as if she felt her role was to keep the five of us focussed on laboratory business. What we were doing was far closer to the purpose of the laboratory than the daily work of designing bunkers and tunnels that was going on around us but Vickie wasn't quite sure. Nevertheless, she was awed by our ability to fill blackboards with equations and addressed us respectfully as Dr. Clavelli, Dr. Gordon etc. We, of course, referred to each other more informally. It was Dr. Lou, Dr. Dave, Dr. Pierre, Dr. Jim, and Dr. Don.

In addition to the theorists, there was a much larger contingent of bright young experimentalists at Fermilab from the beginning. The best of these, or at least the ones who were friendliest to theorists, were Joe Lach, Taiji Yamanouchi, Muzaffer Atac and Dick Carrigan. Taiji was especially known to us as one with boundless empathy for people, especially for people devoted to physics. Muzaffer and his young family resided across from Estelle and me at Carriage Drive.

Bob Wilson, Fermilab's first director, in addition to professing to believe in the importance of theoretical physics, wanted to have a strong experimental physics staff even before the machine was built. He achieved this by hiring experimental physicists for many of the jobs that could have been done, perhaps better, by electrical and civil engineers. In principle they each had 50% time free to pursue experiments at other functioning laboratories but in practice most of them became totally absorbed by the huge task of building the machine. Sometimes Dick Carrigan would pull from his center desk drawer a graph of some data from deep-inelastic scattering suggesting that the intermediate weak boson might be found at a mass of 10 GeV. However, for the most part, it was difficult to engage the experimentalists in discussions about particle physics until the machine was about to turn on.

In the beginning there was a spirit of egalitarianism among the five theorists. Although some of us had had post-doctoral experience and others had come straight from the PhD, there were, as far as we know, no differences in our appointments. However, it was obvious to the lab, if not to us, that a point of contact was needed between the directorate and the theory group. Early in October of 1969, we were told that David Gordon had been chosen to lead the group in this sense. We received the news with indifference. None of us, as far as we knew, had administrative ambitions.

In addition our letters of appointment were vague about the exact nature of our positions. Although speaking of an initial term, they left the clear implication that we were expected to continue at Fermilab. The letters were vague but did not employ the terms in common usage then as now to indicate a strictly term appointment. For instance there was no use of the terms "Post-doctoral" or "Research Associate". In a tenure track appointment at a university, the awardee is to be considered for tenure after five years, even though at many if not all, there is an annual "retention" review. It seemed to us that our letters of appointment might have been the laboratory equivalent of this. We were, at first, indifferent to this vagueness. Although supposedly 1967 had been the last of the good years, we were totally ignorant of the collapse of the job market for theoretical physicists which was going on around us. Full of self confidence, we felt no need for job guarantees from the lab. We had all gone to graduate school in years when the job opportunities for theoretical physicists were seemingly growing without bound. I remember once in early 1969 meeting a panicked young physicist at Yale who had already sensed the growing crisis. I confidently assured him that there were plenty of universities seeking to build physics programs. His response was that that was OK for me but he had been a student at Yale and was expected by his family to become an ivy league professor.

There was always a religious aura surrounding Fermilab. The director's complex was the "Curia". Perhaps we have now totally confused the public by telling them that Fermilab is searching for the "God Particle". At any rate, in the late sixties, the praise of Bob Wilson resounded throughout Fermilab Village and the whole physics community. It would be a pale comparison to equate his status with that of the leader of the Roman Curia. It was said that the Fermilab hi-rise, then under construction, was purposely designed with some of the overtones of the medieval cathedrals. Everyone was free to construct his own private interpretation of this. I always took it to represent the hope that modern society would devote a similar percentage of its GNP to idealistic enterprises as the medieval societies did in building the cathedrals.

In the spring of 1970, at my parents' house in Maryland, I met my uncle who was head of the San Francisco branch of the General Accounting Office. I was singing the praises of Bob Wilson to him. Bob had an ingenious method of dividing big contracts into three parts with the first two parts going to the two lowest bidders and the third going to the one of the two who performed best. My uncle had some doubts whether a machine built like that would ever work but, in any case, he asked me to alert him to any financial improprieties at Fermilab. I made it clear that there could never be scandals of that sort at Bob Wilson's Fermilab. I didn't tell him that Bob had illegally allowed farmers to grow federally subsidized corn on government land. Actually Bob had promptly discontinued the practice as soon as its illegality came to his attention. In the Fall of 1969, hunting was also officially banned on Fermilab land initiating the move to allow the land to revert to its original prairie nature which is largely responsible for the current beauty of the site.

In addition to being a great accelerator builder, Wilson appreciated the importance of art to science. Both require looking at things in new ways. Bob brought with him from Cornell a full time artist in residence, Angela Gonzalez, although, as far as the federal government knew, she was a "librarian". Together they designed the Fermilab logo and many of the sculptures scattered around the site including some graceful structures supporting power lines.

I always thought there should have been some appropriate inscription at the main entrance to Fermilab. I would have suggested the words of King Priam to Helen of Troy from the Iliad Book 3,

In addition to being a great accelerator builder, Wilson appreciated the importance of art to science. Both require looking at things in new ways. Bob brought with him from Cornell a full time artist in residence, Angela Gonzalez, although, as far as the federal government knew, she was a "librarian". Together they designed the Fermilab logo and many of the sculptures scattered around the site including some graceful structures supporting power lines.

I always thought there should have been some appropriate inscription at the main entrance to Fermilab. I would have suggested the words of King Priam to Helen of Troy from the Iliad Book 3,

I have also always been struck by the absence of a suitable statue or portrait of Fermi at Fermilab. It presumably would have been willingly funded by Italian-American groups. Fermi is certainly the greatest physicist to have ever worked in the Chicago area but it has always been clear that the dominant cult at Fermilab is not that of Fermi.

Eventually, in mid fall of 1969, we and especially Pierre felt that we should have some clarification of our status. David, our liaison, was asked to broach the subject in the Curia. The response was not long in coming. Ned Goldwasser through David Gordon assured us that we were on the same appointments as the experimentalists with an "up or out" decision to be made after five years. That confirmed our impressions and perhaps gave us a heightened feeling of pride in being an intrinsic part of the growing laboratory. No one felt it was necessary to insult the Curia by asking to have that put in writing.

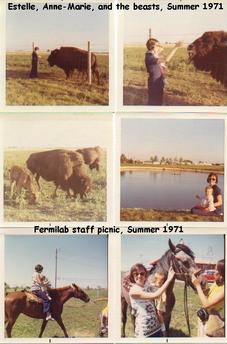

Ned Goldwasser was Bob Wilson's point man. It was widely known that decisions in the Curia were made by only one man and part of Ned's job was to take the heat for mistakes and unpopular decrees. Ned was straight-forward, optimistic, approachable, and well-liked. Bob Wilson, on the other hand was mercurial and cavalier. Although the director's complex had been constructed by picking up some of the Village houses and arranging them in a connected circle, no one, except maybe Pierre, had the illusion that they symbolized an Arthurian round table. One time at lunch Bob was expounding his view that theorists should have no doors on their offices in order to maximize interactions. Pierre remarked that he didn't think that was a good idea. This comment provoked a painful silence. At Fermilab all of Bob's ideas were good by definition. On another occasion, Bob joked that each year the staff would be put in the center of the main ring with the buffalo and those that escaped the ring would be kept on for another year. This system had the potential to save the laboratory from a lot of expensive paperwork. One needed only to hope that the buffalo wouldn't become too tame in captivity to perform this role.

Eventually, in mid fall of 1969, we and especially Pierre felt that we should have some clarification of our status. David, our liaison, was asked to broach the subject in the Curia. The response was not long in coming. Ned Goldwasser through David Gordon assured us that we were on the same appointments as the experimentalists with an "up or out" decision to be made after five years. That confirmed our impressions and perhaps gave us a heightened feeling of pride in being an intrinsic part of the growing laboratory. No one felt it was necessary to insult the Curia by asking to have that put in writing.

Ned Goldwasser was Bob Wilson's point man. It was widely known that decisions in the Curia were made by only one man and part of Ned's job was to take the heat for mistakes and unpopular decrees. Ned was straight-forward, optimistic, approachable, and well-liked. Bob Wilson, on the other hand was mercurial and cavalier. Although the director's complex had been constructed by picking up some of the Village houses and arranging them in a connected circle, no one, except maybe Pierre, had the illusion that they symbolized an Arthurian round table. One time at lunch Bob was expounding his view that theorists should have no doors on their offices in order to maximize interactions. Pierre remarked that he didn't think that was a good idea. This comment provoked a painful silence. At Fermilab all of Bob's ideas were good by definition. On another occasion, Bob joked that each year the staff would be put in the center of the main ring with the buffalo and those that escaped the ring would be kept on for another year. This system had the potential to save the laboratory from a lot of expensive paperwork. One needed only to hope that the buffalo wouldn't become too tame in captivity to perform this role.

Fermilab Theory before the First Beam

Settling in at 27 Sauk, most of us initially pursued the calculations we had come with. However, a natural collaboration developed immediately between David and Pierre. David had co-authored an important paper with Fubini and Veneziano on the operator factorization of the dual resonance models (DRM). Pierre had also been working on the DRM since that summer in Trieste. It was an explosively developing field. The construction of the harmonic oscillator formalism by Fubini and Veneziano led to Nambu and Goto's recognition of the theory as one of relativistic strings. In 1969 and 70, most students of the field felt that Veneziano would ultimately get the Nobel prize for discovering the prototype dual model. No discovery, of course, is without roots. The dual models were an outgrowth of the Finite Energy Sum Rules and much pains-taking analysis of the duality between Regge-Poles and resonances. Veneziano had been working in the scientifically fertile group of Hector Rubinstein at the Weizmann Institute in Israel together with Virasoro and Ademollo. The micro-history of this collaboration would undoubtedly make an interesting story. Subsequent revolutionary developments in string theory have, perhaps unfairly, somewhat eclipsed the original discovery of the dual model.

Getting back to the Fermilab story, on the transatlantic trip back from Europe, Pierre found in the ship's library an open copy of a work of Fubini and Veneziano. Amazed at the unexpected intellectual level of the ship's clientele, Pierre investigated further and ultimately met Andre Neveu who was going to America to take up a post-doctoral position at Princeton.

In November of 1969, Gordon and Ramond wrote the first Fermilab theory paper "A Spinor Formulation for Dual Resonance Models" published in the comments and addenda section of the Physical Review. I was, by then, convinced that dual models were here to stay. I swept all my accumulated notes into folders, never to be looked at again, and began working daily with Dave and Pierre. In those days, one week's worth of dedicated effort was enough to learn all that had been written about dual models. I initially rebelled at the dual model habit of normalizing the Regge slope to 1/2. I knew well that the experimental slope of the trajectories was about 1 in units of GeV^(-2). Once I swallowed that seemingly unnatural normalization, the rest was not difficult.

Gradually, however, a rift developed between Dave and the rest of the group which was most acute in the relation between Dave and Pierre. David's administrative chores were minimal and did not have to affect his physics. However, he seemed sometimes to relish his administrative role more than the physics research we were engaged in. In addition to managing the professor of the month program, Dave started to promote a new technology known as the "electric blackboard" which would allow equations written at a seminar to be transmitted across phone lines together with audio. He spent considerable time trying to set up a connection whereby we could participate in MIT theory seminars through this technology. The device was exceedingly primitive compared to today's webcasting but its ultimate demise was blamed on the assumed reluctance of MIT seminar speakers to have their results broadcast to anonymous listeners in other parts of the country. There was also a plan, known as the Marshak Plan, to develop a large CERN-type theory program at Fermilab. David was enthusiastic about this and several gatherings were scheduled to discuss it. The plan proposed a permanent group of 24 senior theorists including six in areas peripheral to particle physics. In addition 20 post-doctoral research associates and fifty visiting scientists were envisioned which would have made Fermilab the world's preeminent center for particle theory significantly surpassing CERN. Among the "peripheral" areas mentioned were astrophysics and cosmology foreshadowing the current effort at Fermilab in these areas although they can no longer be considered peripheral to particle physics. Ultimately the plan was discarded largely because the neighboring universities wanted Fermilab to remain primarily a user's facility. This was a foolish mistake since the plan would have given a big boost to American theoretical physics at a critical time. Bob Wilson could have pushed it through but, given that he has done so much for US particle physics, he is entitled to have made a few mistakes. A much greater one was conceding the leadership in experimental physics also to CERN in the mid 70's by forcing Rubbia and McIntyre to take their antiproton cooling idea to CERN.

It got to the point where Pierre and I were working at home each evening pursuing the dual resonance models. In the morning we would come together with David and put our results on the board. At 27 Sauk we had every possible square foot of wall space covered by blackboards. It was a pre-cursor of the floor to ceiling blackboards in the theory wing of the present Fermilab hi-rise. After lunch, Pierre and I would go back to work in our offices and David, it seemed, would get on the phone with Fubini and Veneziano. The situation couldn't continue. Eventually Pierre declared that he could no longer collaborate with David. For me the choice between physics and the electric blackboard was an easy one. I opted to continue working with Pierre.

In December of 1969 the group had a meeting with Ned Goldwasser concerning the theory work. Perhaps in retrospect we might have taken some of his statements as a warning of possible troubles to come. We were too young and politically oblivious to discern these warnings if warnings they were. At any rate, Ned told us that Bob Wilson felt that the primary work of the theory group was expected to be directly related to the experimental program. On the other hand, he said, if some truly outstanding work of a more formal nature could be accomplished, that was OK too. We were not at all disturbed. Pierre and I were not sure whether dual models were considered phenomenological or formal but, in any case, we had no intention of doing less than outstanding work. In fact, the whole thrust of dual models in those days was to construct a phenomenologically viable theory for hadronic interactions. I had a list of some twenty reasons to believe that hadronic interactions were described by a dual model. This remains to this day a side-lined but potentially important avenue for string theory research.

Don Weingarten was the most formal of the five of us. What most physicists were content to call a "function" Don insisted on referring to as an "analytic map". He had previously made his opinion clear to us that we didn't really need the accelerator because there was already enough data available to keep theorists busy for decades. In view of the revolution in our understanding of particle physics that has come about in the last thirty years due to experimentation at accelerators, I suspect that Don is not proud of his statement. In fact, it is interesting to wonder which revolutionary new discoveries we are now ignorant of due to the killing of the Super Collider. After Texas was chosen for the SSC site around 1990, I heard an echo of Don's remark emanating from Fermilab: "Maybe we don't need the SSC that much after all". In spite of his predilection toward mathematical physics, Don was, in fact, doing quite phenomenological work. His first Fermilab paper in January of 1970 was on "Large-Angle Scattering by Optical Potentials" and the following month he put out a preprint on "An Optical Model of Elastic Proton-Proton Scattering". Jim Swank was also doing very phenomenological work. His first Fermilab preprint appearing in March 1970 was on "Chiral Dynamics, SU(3)xSU(3) Symmetry Breaking and Kl4 Axial Vector Form Factors".

It is obvious to all physicists that there is a surpassingly elegant symmetry in the laws of physics. For ages this has been taken by some as indicating the existence of an intelligent designer. Others have held out for the eventual discovery of a symmetry self-generating mechanism. Both groups agree that, if one pursues the path of maximum symmetry in physics, one is likely to be led to the truth. Pierre and I began therefore to study intensely the group theoretical underpinnings of the dual models. The generalized Veneziano model had an SU(1,1) or SL(2,R) symmetry, groups whose unitary irreducible representations had been catalogued by Bargmann and Wigner in the early decades of the twentieth century. Like SU(2) the representations were characterized by a Casimir operator whose eigenvalues were J(J+1). Unlike SU(2), however, J was negative for SU(1,1). The vertex operator for the Veneziano model ground state transformed with SU(1,1) spin -k^2/2. We saw how to generalize Bargmann's invariant product of two representations to a multiple product which was the Veneziano N point function. This formed the core of our first paper in the Spring of 1970. We proceeded to abstract from this a "recipe" for duality which offered the possibility of constructing new dual models. We felt the exhilaration of understanding something that no one else in the world understood. As an example of its power, we used the recipe to write an expression for the dual N point function where the external states were arbitrarily excited particles on the leading Regge trajectory. Due to the intervening Summer Study, the Fermilab preprint, Group Theoretical Construction of Dual Amplitudes, didn't come out, however, until September of 1970. In retrospect, Fubini and Veneziano and, perhaps, Bardakci and Halpern at Berkeley might have been independently coming to much of the same understanding.

Getting back to the Fermilab story, on the transatlantic trip back from Europe, Pierre found in the ship's library an open copy of a work of Fubini and Veneziano. Amazed at the unexpected intellectual level of the ship's clientele, Pierre investigated further and ultimately met Andre Neveu who was going to America to take up a post-doctoral position at Princeton.

In November of 1969, Gordon and Ramond wrote the first Fermilab theory paper "A Spinor Formulation for Dual Resonance Models" published in the comments and addenda section of the Physical Review. I was, by then, convinced that dual models were here to stay. I swept all my accumulated notes into folders, never to be looked at again, and began working daily with Dave and Pierre. In those days, one week's worth of dedicated effort was enough to learn all that had been written about dual models. I initially rebelled at the dual model habit of normalizing the Regge slope to 1/2. I knew well that the experimental slope of the trajectories was about 1 in units of GeV^(-2). Once I swallowed that seemingly unnatural normalization, the rest was not difficult.

Gradually, however, a rift developed between Dave and the rest of the group which was most acute in the relation between Dave and Pierre. David's administrative chores were minimal and did not have to affect his physics. However, he seemed sometimes to relish his administrative role more than the physics research we were engaged in. In addition to managing the professor of the month program, Dave started to promote a new technology known as the "electric blackboard" which would allow equations written at a seminar to be transmitted across phone lines together with audio. He spent considerable time trying to set up a connection whereby we could participate in MIT theory seminars through this technology. The device was exceedingly primitive compared to today's webcasting but its ultimate demise was blamed on the assumed reluctance of MIT seminar speakers to have their results broadcast to anonymous listeners in other parts of the country. There was also a plan, known as the Marshak Plan, to develop a large CERN-type theory program at Fermilab. David was enthusiastic about this and several gatherings were scheduled to discuss it. The plan proposed a permanent group of 24 senior theorists including six in areas peripheral to particle physics. In addition 20 post-doctoral research associates and fifty visiting scientists were envisioned which would have made Fermilab the world's preeminent center for particle theory significantly surpassing CERN. Among the "peripheral" areas mentioned were astrophysics and cosmology foreshadowing the current effort at Fermilab in these areas although they can no longer be considered peripheral to particle physics. Ultimately the plan was discarded largely because the neighboring universities wanted Fermilab to remain primarily a user's facility. This was a foolish mistake since the plan would have given a big boost to American theoretical physics at a critical time. Bob Wilson could have pushed it through but, given that he has done so much for US particle physics, he is entitled to have made a few mistakes. A much greater one was conceding the leadership in experimental physics also to CERN in the mid 70's by forcing Rubbia and McIntyre to take their antiproton cooling idea to CERN.

It got to the point where Pierre and I were working at home each evening pursuing the dual resonance models. In the morning we would come together with David and put our results on the board. At 27 Sauk we had every possible square foot of wall space covered by blackboards. It was a pre-cursor of the floor to ceiling blackboards in the theory wing of the present Fermilab hi-rise. After lunch, Pierre and I would go back to work in our offices and David, it seemed, would get on the phone with Fubini and Veneziano. The situation couldn't continue. Eventually Pierre declared that he could no longer collaborate with David. For me the choice between physics and the electric blackboard was an easy one. I opted to continue working with Pierre.

In December of 1969 the group had a meeting with Ned Goldwasser concerning the theory work. Perhaps in retrospect we might have taken some of his statements as a warning of possible troubles to come. We were too young and politically oblivious to discern these warnings if warnings they were. At any rate, Ned told us that Bob Wilson felt that the primary work of the theory group was expected to be directly related to the experimental program. On the other hand, he said, if some truly outstanding work of a more formal nature could be accomplished, that was OK too. We were not at all disturbed. Pierre and I were not sure whether dual models were considered phenomenological or formal but, in any case, we had no intention of doing less than outstanding work. In fact, the whole thrust of dual models in those days was to construct a phenomenologically viable theory for hadronic interactions. I had a list of some twenty reasons to believe that hadronic interactions were described by a dual model. This remains to this day a side-lined but potentially important avenue for string theory research.

Don Weingarten was the most formal of the five of us. What most physicists were content to call a "function" Don insisted on referring to as an "analytic map". He had previously made his opinion clear to us that we didn't really need the accelerator because there was already enough data available to keep theorists busy for decades. In view of the revolution in our understanding of particle physics that has come about in the last thirty years due to experimentation at accelerators, I suspect that Don is not proud of his statement. In fact, it is interesting to wonder which revolutionary new discoveries we are now ignorant of due to the killing of the Super Collider. After Texas was chosen for the SSC site around 1990, I heard an echo of Don's remark emanating from Fermilab: "Maybe we don't need the SSC that much after all". In spite of his predilection toward mathematical physics, Don was, in fact, doing quite phenomenological work. His first Fermilab paper in January of 1970 was on "Large-Angle Scattering by Optical Potentials" and the following month he put out a preprint on "An Optical Model of Elastic Proton-Proton Scattering". Jim Swank was also doing very phenomenological work. His first Fermilab preprint appearing in March 1970 was on "Chiral Dynamics, SU(3)xSU(3) Symmetry Breaking and Kl4 Axial Vector Form Factors".

It is obvious to all physicists that there is a surpassingly elegant symmetry in the laws of physics. For ages this has been taken by some as indicating the existence of an intelligent designer. Others have held out for the eventual discovery of a symmetry self-generating mechanism. Both groups agree that, if one pursues the path of maximum symmetry in physics, one is likely to be led to the truth. Pierre and I began therefore to study intensely the group theoretical underpinnings of the dual models. The generalized Veneziano model had an SU(1,1) or SL(2,R) symmetry, groups whose unitary irreducible representations had been catalogued by Bargmann and Wigner in the early decades of the twentieth century. Like SU(2) the representations were characterized by a Casimir operator whose eigenvalues were J(J+1). Unlike SU(2), however, J was negative for SU(1,1). The vertex operator for the Veneziano model ground state transformed with SU(1,1) spin -k^2/2. We saw how to generalize Bargmann's invariant product of two representations to a multiple product which was the Veneziano N point function. This formed the core of our first paper in the Spring of 1970. We proceeded to abstract from this a "recipe" for duality which offered the possibility of constructing new dual models. We felt the exhilaration of understanding something that no one else in the world understood. As an example of its power, we used the recipe to write an expression for the dual N point function where the external states were arbitrarily excited particles on the leading Regge trajectory. Due to the intervening Summer Study, the Fermilab preprint, Group Theoretical Construction of Dual Amplitudes, didn't come out, however, until September of 1970. In retrospect, Fubini and Veneziano and, perhaps, Bardakci and Halpern at Berkeley might have been independently coming to much of the same understanding.

Early in 1970, the theory group had left the house on Sauk and moved into the Curia complex immediately adjacent to the directorate. We took this as indicating that the status of theory was rising the closer one came to having a real accelerator.

As mentioned, there was a brief hiatus in our work on dual models due to the summer study of 1970. A large contingent of physicists from around the country descended on the laboratory to discuss the experiments expected to begin late in the following year. Prominent among them was Bob Panvini who went on to play a leading role in the development of particle physics in the Southeast. Also there, working energetically, was Jim Trefil from Illinois who has now made a name for himself in the popularization of modern physics. Don Weingarten couldn't resist the quip "Don't trifle with Trefil".

As mentioned, there was a brief hiatus in our work on dual models due to the summer study of 1970. A large contingent of physicists from around the country descended on the laboratory to discuss the experiments expected to begin late in the following year. Prominent among them was Bob Panvini who went on to play a leading role in the development of particle physics in the Southeast. Also there, working energetically, was Jim Trefil from Illinois who has now made a name for himself in the popularization of modern physics. Don Weingarten couldn't resist the quip "Don't trifle with Trefil".

|

I was part of a ten man committee examining the potential for Neutrino Bubble Chamber Physics. With Rod Engelmann from Stony Brook, I wrote an article on "Theoretical Questions and Measurements of Neutrino Reactions in Bubble Chambers". In addition Jim Swank and I wrote a short paper on the "Hadronic Branching Ratio of the W Boson". Jim was also heavily involved in reviewing proposals for the first round of experiments. The summer study was eventually published in a comprehensive volume with a cover by Angela Gonzalez.

I never saw a computer at Weston. If we needed to do any numerical work we used a slide rule not very different from the one Fermi used some thirty years earlier. Some of the more favored experimentalists had Wang calculators. Anything more serious involved carrying a deck of computer punch cards to Argonne Laboratory for processing. |

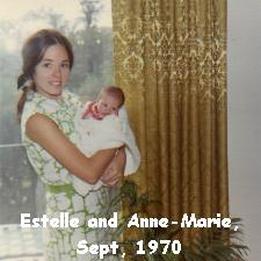

In August of that year, A-M Clavelli was born in the St. Charles hospital, the first child of a Fermilab theorist. Estelle and I later had a second daughter and Pierre and Lillian had three. We joked that Regge theorists had mainly daughters, referring to the infinite numbers of daughter trajectories in dual models.

In the fall, Pierre and I resumed our work on the group theoretical basis for dual models. With our new understanding, the way was wide open for the construction of new dual models. We combed the libraries in Chicago for new representations of the SU(1,1) algebra. However storm clouds were gathering at Fermilab.

In October of 1970, David Gordon came to me with a strange question. What did I take as the meaning of the statement from Ned Goldwasser that we theorists were on track with the experimentalists toward a permanent appointment? With incredible naivete, I answered that that was just an oral statement without any legal weight. Although I couldn't interpret the strange smile with which David left, neither could I imagine that the laboratory could dispense with our theoretical work nor easily replace us.

On November 2, 1970 the unexpected blow fell. The four of us were presented with white envelopes. I was the last to open the envelope but I could tell from the pale expressions around me that something was seriously wrong. The four of us had received identical letters signed by Edwin L. Goldwasser informing us that we were being terminated as of September 1971. Only David Gordon was being kept on. The sole reason quoted for the termination was that "..we had hoped that considerably stronger interactions would develop between you and the experimental physicists than has been the case... It is pretty clear that our experiment has not been a total success, and it would be foolish to pretend otherwise."

Our sense of betrayal was very strong. Something did not ring true. The reason cited did not seem fair given the nearly total preoccupation of the experimentalists with the building of the accelerator. We could not imagine that the experimentalists had accused us of being uncooperative or unhelpful. The laboratory had a list of eighteen theoretical advisors from around the midwest, many of whom we knew well. The only theoretical consultant that we had seen at the lab in that capacity was Bob Serber. We could not imagine any of these advising that we be dismissed. There was, however, in some other quarters of the physics community an irrational distaste for dual models that might have played a role. Sam Treiman had declared that no one doing dual models would ever be allowed to get tenure at Princeton. Another unknown was what kind of reports David had been submitting regarding us. Nevertheless, there was little open hostility between David and us. David had the laboratory install a blackboard at his home and we would periodically meet in the evening with the experimentalists at the yellow stucco house to discuss future experiments.

Bob Serber met with us toward the end of November 1970 to explain the laboratory position. He indicated that he expected "the laboratory would continue its post-doctoral theory program". We were outraged and reacted angrily! That was the first time we had been referred to as post-docs. We could handle being terminated but not having our positions retroactively redefined for the convenience of the directorate. If we had been post-docs we would have begun our job search much earlier in the fall and Jim and Jean would not have bought the house they did a few months prior to our termination letter. In fact, post-docs do not normally get termination letters especially ones citing reasons for dismissal. The following month I happened to be sitting next to Peter Rosen on a bus at a physics conference. I casually mentioned to him what had happened and he was totally shocked. With his broader experience he seemed to understand better than we what was happening. With the job situation tightening rapidly and the machine about to turn on, the five theory positions at Fermilab had perhaps become valuable to the eastern establishment.

Due, maybe, to the new stress in our lives Pierre and I began collaborating less closely. In Volume IX of the Boulder lectures in theoretical physics I had found an article by Barut discussing the construction of operator representations of SU(1,1). It was clear that these could be used to build vastly different dual models from that of Veneziano. One of the big questions in dual theory was how to obtain the half integer spacing between the pi and rho trajectories that was seen experimentally. The Veneziano model had only integer spacing. I tried to interest Pierre in using the 1/2 integer moded representations to build such a model.

Pierre, meanwhile, had put aside our "recipe" for dual models and was working to develop a theory of fermions. He had earlier been fascinated by the aspect of the particle momentum being the average of the string operator, P_mu. He developed a new operator whose average was the Dirac gamma matrix. It was, for lack of a more meaningful term, a stroke of genius. Pierre's construction contained a new algebra which amounted to the first appearance of a supersymmetry in string theory. A marginally earlier work by Gol'fand and Likhtman had also introduced a supersymmetry into physics without the connection with duality of Pierre's paper. This Russian paper was unknown to us and to most of the physics community for quite some time and did not lead to the immediate developments that Pierre's paper triggered.

I was concerned that the SU(1,1) generators in Pierre's algebra did not annihilate the vacuum and, therefore, could not be used to construct new dual models according to the recipe. We traveled to the Fermi Institute in Chicago where Pierre explained his construction to Nambu and I voiced my reservations. With characteristic insight Nambu suggested that my concerns might be somehow overcome as indeed turned out to be the case after later works by Andre Neveu, John Schwarz, Charles Thorn and others.

In October of 1970, David Gordon came to me with a strange question. What did I take as the meaning of the statement from Ned Goldwasser that we theorists were on track with the experimentalists toward a permanent appointment? With incredible naivete, I answered that that was just an oral statement without any legal weight. Although I couldn't interpret the strange smile with which David left, neither could I imagine that the laboratory could dispense with our theoretical work nor easily replace us.

On November 2, 1970 the unexpected blow fell. The four of us were presented with white envelopes. I was the last to open the envelope but I could tell from the pale expressions around me that something was seriously wrong. The four of us had received identical letters signed by Edwin L. Goldwasser informing us that we were being terminated as of September 1971. Only David Gordon was being kept on. The sole reason quoted for the termination was that "..we had hoped that considerably stronger interactions would develop between you and the experimental physicists than has been the case... It is pretty clear that our experiment has not been a total success, and it would be foolish to pretend otherwise."

Our sense of betrayal was very strong. Something did not ring true. The reason cited did not seem fair given the nearly total preoccupation of the experimentalists with the building of the accelerator. We could not imagine that the experimentalists had accused us of being uncooperative or unhelpful. The laboratory had a list of eighteen theoretical advisors from around the midwest, many of whom we knew well. The only theoretical consultant that we had seen at the lab in that capacity was Bob Serber. We could not imagine any of these advising that we be dismissed. There was, however, in some other quarters of the physics community an irrational distaste for dual models that might have played a role. Sam Treiman had declared that no one doing dual models would ever be allowed to get tenure at Princeton. Another unknown was what kind of reports David had been submitting regarding us. Nevertheless, there was little open hostility between David and us. David had the laboratory install a blackboard at his home and we would periodically meet in the evening with the experimentalists at the yellow stucco house to discuss future experiments.

Bob Serber met with us toward the end of November 1970 to explain the laboratory position. He indicated that he expected "the laboratory would continue its post-doctoral theory program". We were outraged and reacted angrily! That was the first time we had been referred to as post-docs. We could handle being terminated but not having our positions retroactively redefined for the convenience of the directorate. If we had been post-docs we would have begun our job search much earlier in the fall and Jim and Jean would not have bought the house they did a few months prior to our termination letter. In fact, post-docs do not normally get termination letters especially ones citing reasons for dismissal. The following month I happened to be sitting next to Peter Rosen on a bus at a physics conference. I casually mentioned to him what had happened and he was totally shocked. With his broader experience he seemed to understand better than we what was happening. With the job situation tightening rapidly and the machine about to turn on, the five theory positions at Fermilab had perhaps become valuable to the eastern establishment.

Due, maybe, to the new stress in our lives Pierre and I began collaborating less closely. In Volume IX of the Boulder lectures in theoretical physics I had found an article by Barut discussing the construction of operator representations of SU(1,1). It was clear that these could be used to build vastly different dual models from that of Veneziano. One of the big questions in dual theory was how to obtain the half integer spacing between the pi and rho trajectories that was seen experimentally. The Veneziano model had only integer spacing. I tried to interest Pierre in using the 1/2 integer moded representations to build such a model.

Pierre, meanwhile, had put aside our "recipe" for dual models and was working to develop a theory of fermions. He had earlier been fascinated by the aspect of the particle momentum being the average of the string operator, P_mu. He developed a new operator whose average was the Dirac gamma matrix. It was, for lack of a more meaningful term, a stroke of genius. Pierre's construction contained a new algebra which amounted to the first appearance of a supersymmetry in string theory. A marginally earlier work by Gol'fand and Likhtman had also introduced a supersymmetry into physics without the connection with duality of Pierre's paper. This Russian paper was unknown to us and to most of the physics community for quite some time and did not lead to the immediate developments that Pierre's paper triggered.

I was concerned that the SU(1,1) generators in Pierre's algebra did not annihilate the vacuum and, therefore, could not be used to construct new dual models according to the recipe. We traveled to the Fermi Institute in Chicago where Pierre explained his construction to Nambu and I voiced my reservations. With characteristic insight Nambu suggested that my concerns might be somehow overcome as indeed turned out to be the case after later works by Andre Neveu, John Schwarz, Charles Thorn and others.

About the same time, Bardakci and Halpern came out with an article on "New Dual Quark Models" using the half integer modedrepresentation. In those days communication of scientific results was some thirty to forty times slower than today. I was angry at myself for not writing up my ideas earlier and hastily wrote some of my constructions in a paper entitled "New Dual N-Point Functions" including some using quarter integer representations of the algebra that had the half integer trajectory splitting and some others that provided a model for the splitting between the pi and K trajectories. I made a mistake in the paper by assuming that the Virasoro generators could be constructed by the standard techniques for the quarter integer models which turned out not to be true. Virasoro called me from Berkeley to quiz me on this point. Probably my erroneous statement had caused him some loss of time. Pierre reviewed the models in his Boulder lectures in the summer of 1971, but the absence of the Virasoro generators meant that the quarter integer models were hopelessly infected by unphysical states.

Pierre and I could have easily written the Neveu-Schwarz model which soon appeared from Princeton. Andre Neveu came to Fermilab and presented a seminar on the work that he and John Schwarz had done. It was obvious to Pierre that the Neveu-Schwarz model was a clear example of our recipe for duality. I explained it to David Gordon. The Neveu-Schwarz model was based on SU(1,1) spinor, Lorentz vector representations. I had earlier casually written a model with SU(1,1) spinor, Lorentz scalar representations which also had the half integer splitting.

On the last night of 1970, Estelle and I threw a party for the four discharged theorists and spouses. By then the seriousness of our situation had dawned on us. The market for theoretical physics had apparently totally collapsed. There were extremely few advertisements in Physics Today for theorists. Estelle had often joked about "physics parties". They often seemed to consist of guys sitting around in a circle exchanging barbed comments about physics or the Vietnam war. This evening was far worse than usual. It was certainly not the typical New Year's Eve soiree going on that evening throughout Chicagoland. Don was slumped listlessly on our couch with his feet on the coffee table. Most of the talk was about the job situation. Still there was no discussion of the possibility of seeking a job in industry. We wondered whether we could find a job by writing to a hundred universities or whether we needed to consider small colleges also and therefore needed to write a thousand letters. In either case finding a job was going to be a gargantuan task in those days of no word processors. At midnight we had some champagne and Estelle and I briefly kissed.

With the help of the laboratory, we maintained a good sense of humor into the early months of 1971. In January the laboratory wrote a letter to the Selective Service System on behalf of Pierre: "We respectfully request that the current occupational deferment be extended for Dr. Ramond. Dr. Ramond has brought to this Laboratory a background difficult to duplicate. This, coupled with one year's experience gained working on design features of this machine are impossible to replace. The loss of his services would severely hamper the operation of the accelerator at the nation's newest national laboratory."

Omitted was the line: "And by the way, Dr. Ramond will be available for service in Vietnam as of September 1 since we have fired him as of that date".

Evidently Pierre had been living a double life, grappling with string theory all day but totally absorbed by accelerator design problems all night. Actually, none of the five of us had the foggiest idea of how to build a real accelerator. If we had thought that any of Pierre's ideas had been incorporated into the design of the machine we might have been glad we were leaving before the turn-on. Perhaps in fact, our not becoming involved in the accelerator design was partially responsible for the fact that the machine turned on eventually at twice the design energy, 450 GeV (or BeV as one then said) instead of 225 GeV.

Pierre and I could have easily written the Neveu-Schwarz model which soon appeared from Princeton. Andre Neveu came to Fermilab and presented a seminar on the work that he and John Schwarz had done. It was obvious to Pierre that the Neveu-Schwarz model was a clear example of our recipe for duality. I explained it to David Gordon. The Neveu-Schwarz model was based on SU(1,1) spinor, Lorentz vector representations. I had earlier casually written a model with SU(1,1) spinor, Lorentz scalar representations which also had the half integer splitting.

On the last night of 1970, Estelle and I threw a party for the four discharged theorists and spouses. By then the seriousness of our situation had dawned on us. The market for theoretical physics had apparently totally collapsed. There were extremely few advertisements in Physics Today for theorists. Estelle had often joked about "physics parties". They often seemed to consist of guys sitting around in a circle exchanging barbed comments about physics or the Vietnam war. This evening was far worse than usual. It was certainly not the typical New Year's Eve soiree going on that evening throughout Chicagoland. Don was slumped listlessly on our couch with his feet on the coffee table. Most of the talk was about the job situation. Still there was no discussion of the possibility of seeking a job in industry. We wondered whether we could find a job by writing to a hundred universities or whether we needed to consider small colleges also and therefore needed to write a thousand letters. In either case finding a job was going to be a gargantuan task in those days of no word processors. At midnight we had some champagne and Estelle and I briefly kissed.

With the help of the laboratory, we maintained a good sense of humor into the early months of 1971. In January the laboratory wrote a letter to the Selective Service System on behalf of Pierre: "We respectfully request that the current occupational deferment be extended for Dr. Ramond. Dr. Ramond has brought to this Laboratory a background difficult to duplicate. This, coupled with one year's experience gained working on design features of this machine are impossible to replace. The loss of his services would severely hamper the operation of the accelerator at the nation's newest national laboratory."

Omitted was the line: "And by the way, Dr. Ramond will be available for service in Vietnam as of September 1 since we have fired him as of that date".

Evidently Pierre had been living a double life, grappling with string theory all day but totally absorbed by accelerator design problems all night. Actually, none of the five of us had the foggiest idea of how to build a real accelerator. If we had thought that any of Pierre's ideas had been incorporated into the design of the machine we might have been glad we were leaving before the turn-on. Perhaps in fact, our not becoming involved in the accelerator design was partially responsible for the fact that the machine turned on eventually at twice the design energy, 450 GeV (or BeV as one then said) instead of 225 GeV.

As if to make our fall from favor totally clear, the theory group was moved out of the Curia complex and into a house across the street at 33 Shabbona. Today the house is quite nice, shaded by mature trees, but in 1971, it was essentially in a gravel parking lot. As might have been expected, growing as it did out of a corn field, the Fermilab Village had a serious rodent problem. Occasionally some maintainance men would come around and dump a pile of rat poison in our closet. Once, while I was working late in my office, I turned around to see a small mouse crouched in the middle of the floor about five feet from my desk. He was quite sick and wanted me, apparently, to plead his case with the laboratory management. I, of course, had no further clout in the Curia. The next day he was gone. On another occasion, looking out our window at 33 Shabbona at dusk, I saw a large rat or similar animal run down the Curia steps. The following year at Rutgers, John Bronzan accused me of fabricating an allegory in this story but it was true.

Throughout the winter and into the Spring Pierre and I continued to talk about dual models but the old dynamic was gone. We did succeed in writing one further article together about currents in dual models but a lot of time was being spent pursuing job prospects. To relieve the stress we played tennis and ate Lillian's Baba au Rhum. David had entered into physics discussions with Paul Frampton then a Post-doc at the University of Chicago.

There had been a period of raised hopes based on Ron Aaron's Particle and Nuclear Physics Pool (PNPP). Ron, a professor at Northeastern University, had an idea to remove some of the unnecessary defects of the job market by computerizing the game. Each candidate would send their application to Ron with an ordered list of their preferences for the available jobs. Ron would distribute their applications to the schools and receive from them an ordered list of their preferred candidates. At the stroke of midnight on some predetermined date, a computer would match candidates to schools. In this way no candidate would lose his preferred job because some less preferred school was demanding a decision. Also no school would lose a second choice because their first choice was holding out for some other opportunity. In theory every candidate and every school would get the best outcome possible for them with much less paperwork. The problem, of course, was that there were only five faculty jobs in the pool and twelve temporary jobs. When the time came the jobs were gone at one second after midnight and hundreds of good theorists were still without jobs.

Although the job market for theorists never recovered its pre-1967 vitality, the period around 1970 is still the all time worst depression in particle theory not only in the sheer magnitude of the problem but in the surprise factor. From World War II until the mid sixties, the job market for young theorists had grown seemingly without bound. In graduate school I never heard a student worry out loud about job prospects in academia. Nambu and Wightman wrote a report on the crisis for NSF in April 1970 with a followup survey in December 1970. They found that over 600 applicants had applied to 51 major research centers in the US where only 85 postdoctoral and junior faculty openings were available. Only a very small fraction of these openings were advertised. After reviewing the evaluations supplied by the reporting institutions, Nambu and Wightman judged that 140 of these applicants, were "class A" theorists many of whom were obviously going to be forced out of physics.

Throughout the winter and into the Spring Pierre and I continued to talk about dual models but the old dynamic was gone. We did succeed in writing one further article together about currents in dual models but a lot of time was being spent pursuing job prospects. To relieve the stress we played tennis and ate Lillian's Baba au Rhum. David had entered into physics discussions with Paul Frampton then a Post-doc at the University of Chicago.

There had been a period of raised hopes based on Ron Aaron's Particle and Nuclear Physics Pool (PNPP). Ron, a professor at Northeastern University, had an idea to remove some of the unnecessary defects of the job market by computerizing the game. Each candidate would send their application to Ron with an ordered list of their preferences for the available jobs. Ron would distribute their applications to the schools and receive from them an ordered list of their preferred candidates. At the stroke of midnight on some predetermined date, a computer would match candidates to schools. In this way no candidate would lose his preferred job because some less preferred school was demanding a decision. Also no school would lose a second choice because their first choice was holding out for some other opportunity. In theory every candidate and every school would get the best outcome possible for them with much less paperwork. The problem, of course, was that there were only five faculty jobs in the pool and twelve temporary jobs. When the time came the jobs were gone at one second after midnight and hundreds of good theorists were still without jobs.

Although the job market for theorists never recovered its pre-1967 vitality, the period around 1970 is still the all time worst depression in particle theory not only in the sheer magnitude of the problem but in the surprise factor. From World War II until the mid sixties, the job market for young theorists had grown seemingly without bound. In graduate school I never heard a student worry out loud about job prospects in academia. Nambu and Wightman wrote a report on the crisis for NSF in April 1970 with a followup survey in December 1970. They found that over 600 applicants had applied to 51 major research centers in the US where only 85 postdoctoral and junior faculty openings were available. Only a very small fraction of these openings were advertised. After reviewing the evaluations supplied by the reporting institutions, Nambu and Wightman judged that 140 of these applicants, were "class A" theorists many of whom were obviously going to be forced out of physics.

In the end, however, the four theorists at Fermilab found jobs with good research opportunities. Pierre and I had been at a New York APS meeting when our return flight was cancelled due to weather. I suggested we use the opportunity to visit Yale where I introduced him to the theory group. Pierre gave a talk and shortly thereafter he was offered a job in New Haven. Pierre has several times since then returned the favor to me. Soon I had a similar offer with Lovelace and Shapiro at Rutgers. Don found a job at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen and Jim moved to the Middle East Technical University to work in the group of Feza Gursey. We had proven ourselves to be more agile than the buffalo but we were not staying on. At Rutgers there was a refreshing lack of ambiguity about my post. This time I was a post-doc from the beginning but I enjoyed a good rapport with Claude Lovelace and a fruitful collaboration with Joel Shapiro. In fact, I have now worked for two national labs and seven universities and, at all seven, I have always found the highest ethical standards in the professional dealings and scientific work of the faculty.

I left Fermilab on August 31, 1971. In my exit interview with Ned Goldwasser, I was warmly complimented for my work at the 1970 Summer Study. Ned told me that there had been discussion in the Curia of keeping me on solely because of that work although they later decided that making a clean sweep was better. No mention was made of our work on the group theoretical basis for string theory leading, as it did, to important generalizations of the Veneziano model and ultimately to Pierre's invention of supersymmetry. Our "recipe" for duality is the basis for the bosonic sectors of the current superstrings while Pierre's gamma matrix is the basis for the fermionic sectors. It was clear, however, that the four pages I had written with Jim Swank in the summer study were deemed far more relevant to the lab than the string theory work. It is generally agreed that the most important discoveries to come out of the experimental program at Fermilab were those of the third generation of quarks, Beauty and Truth. The jury is still out, perhaps, on Fermilab's greatest achievement in theory or its overall greatest achievement.